A small flock of clouds kneel above us. It is an August evening; the sky is stained blue, and the streetlights are on. My room is flooded with a red hue emanating from my red lamp and paper lantern. Candles populate the space, lodged in wine bottles that harbour dried wax.

We are, once again, sat in a circle on the floor, my speaker in the middle. Some of us are lying on our front, some cross-legged. When I stop the podcast playing, I ask if anybody is comfortable going first to “embody their object”. Madura offers.

What does it mean to belong when “home” exists only in the form of faded photographs wedged in leather-bound wallets and photo albums or in half-truths of family stories? When home exists only in the fragments told by one’s お父さん (father) across a kitchen table?

*

The teeth of the world are sharp. Borders, passports, and visas sharpen them, ensure they gleam; they dictate and organise how bodies move through the world, how quickly, how easily. While such documents are tangible markers of where we are allowed to belong, they do not lend themselves to malleability: they are rigid, staunchly bureaucratic, indifferent. Instead, can home and belonging, be traced through everyday objects, through storytelling, and imagination?

I wanted to explore what it means to belong amongst the queer diasporic community in Scotland, felt through smell, song, and silver rings, through objects and their own artistic responses.

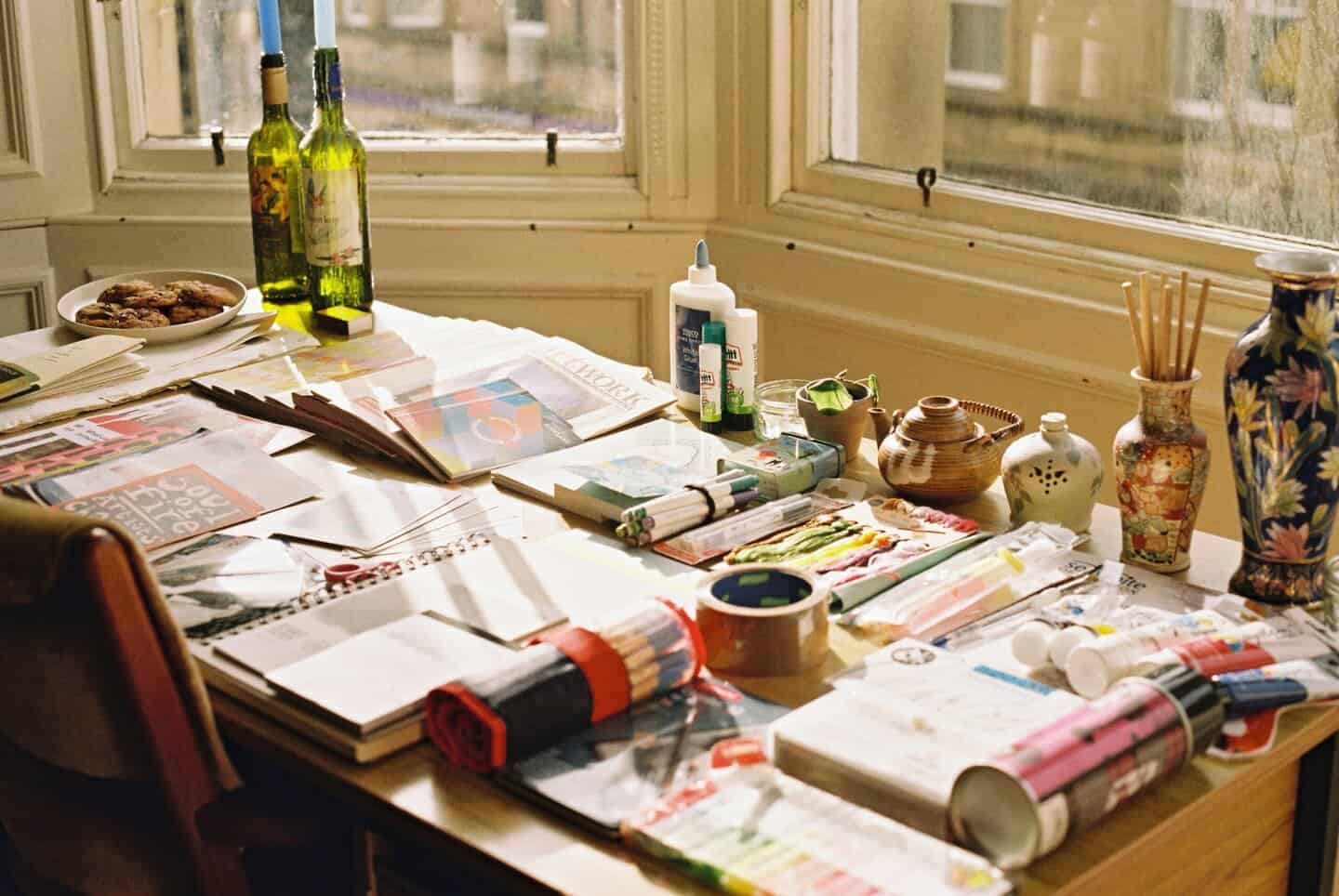

In my research, conducted solely from the confines of my room in Edinburgh , I invited participants – strangers turned friends – to participate in both “object-embodiment” and “artmaking” workshops. For the object-embodiment workshop I borrowed the formula from the podcast, Everything is Alive, which anthropomorphises everyday objects, collapsing humour and profundity to explore how objects mediate human relationships with the world. I asked participants to bring an object that reminded them of home, evoked belonging, or connected them to their cultural heritage.

My second workshop design was a collective workshop grounded in art practice. I prompted participants to create an artwork inquiring ‘What is belonging to you?’ ‘How has your sense of belonging been affected by the current political climate in the UK?’ – a question particularly relevant due my workshops coinciding with the surge of far-right riots in England and Northern Ireland in 2024. Whispers of these riots spreading to Scotland left many of my participants anxious.

The concept of “diasporic longing”: a phrase stated fleetingly by one of the participants Madura was central to the research. It’s a phrase I have come to understand as an ache of partiality and incompleteness that permeates people’s experiences of frayed histories and ephemeral homes.

Madura’s Great-Grandmothers Rings | Photographs by author

Madura, who left India for the UK at a young age, shows us a few silver rings; she fiddles with them as she speaks. They are slightly misshapen; they indicate wear yet remain timeless. For Madura, they are in some ways redundant as they do not fit her fingers but alternatively exist as pieces of art that she exhibits in her room. Madura singles out one ring to discuss. It is silver and elegant with curving protruding lines that wrap around its body, framing a turquoise jewel in the middle. She passes it around while telling us of its history. This was supposedly her great-grandmother’s ring and, despite being contested by Madura’s mother, she likes to imagine it to be so, regardless of the veridic story. It is elegant and she thinks it harbours an accurate representation of her great-grandmother. In her own words, perhaps the insistence of it being her great-grandmother’s pays tribute to the projection of “diasporic longing” onto objects passed down, whereas for our parents’ generation, “it’s not that deep”.

Perhaps, it is the tendency for immigrants to pastoralize a homeland that stays frozen in time, the time they left it. The ring is then perhaps more meaningful or “deeper” to Madura having immigrated from India to the UK at a young age, because she wants to be affected and brought closer to the everyday rhythms of her previous life, as though no time has elapsed between then and now. Thus, the ring transcends its tangibility, symbolic of space between the past and present, concretising the past as a nostalgic and unchanging place. There is refuge to be found in the ring as a piece of home and her matrilineal family on her bedside table.

*

This is the first time I have properly met Kamal. He has dark features and light eyes and grew up in Dubai, before moving to the UK with two Indian parents. Kamal says he feels he has had to choose between his ethnicity and his queerness, stating “I feel like I’ve definitely chosen queerness”. Kamal gestures to his experience of being both queer and Indian, that these two truths cannot overlap but must remain separate. Yet as Kamal presents the rakhis (bracelets), he says “I told my family that I was trans, they were all pretty chill with it, which I’m lucky for – and then my sister and my closest cousins would send me rakhis in the mail which was almost like a gender affirming thing as well as something that’s connecting you to your heritage, which was nice.”

Rakhi is short for Raksha Bandhan translated from Sanskrit “bond of protection”, denoting a ceremony originating with the Hindu faith in India that honours the bond between brothers and sisters. At the heart of this celebration lies the rakhi bracelet, a thread that is tied around the wrist of the brother, followed by an exchange of words on how to best support each other to achieve their life goals. The rakhi is an embodied reminder of a cultural promise, a symbol of protection, of love.

Despite Kamal stating that his queerness and ethnicity cannot overlap, feeling obliged to choose one, the rakhi sent by his sister and closest cousins when he tells his family he is trans materially bridges the two. The rakhi is traditionally given by a sister to her brother, thus making the act of Kamal’s sister and cousins sending Kamal the rakhis all the more significant. Subsequently, an item perhaps previously not queered becomes, in this moment, an object of unconditional acceptance. To belong, for many in the queer diasporic community in Scotland, is not to settle into fixed categories of identity, nation, or home, but to trace meaning in moments of care, community, and gesture: small and fleeting, but carrying the promise of home.

The objects shared in my workshops – whether rings, rakhis, or stories – are not merely relics of a past life or culture, but active agents in the remaking of self and belonging.

This article was written for The Scottish Beacon through a partnership with Pass The Mic Scotland.