This week saw the Spring Collective present ‘a collision of presentations’, song, poetry, provocations and collective imagination in a new form of ‘ceilidh theatre’ all focused on the urgency of Scotland’s energy future.

Taking inspiration from the Scottish Beacon’s Power Shift project, this group, comprising theatre directors, musicians, writers, poets, journalists and researchers, improvised a new form of participation that veered somewhere between Theatre of the Oppressed, a political gathering, a community meeting and a ceilidh.

The event was conceived by a loose collective of people, directed by Simon Sharkey, of The Necessary Space and hosted by Pat Kane and Indra Adnan of the THE ALTERNATIVE.

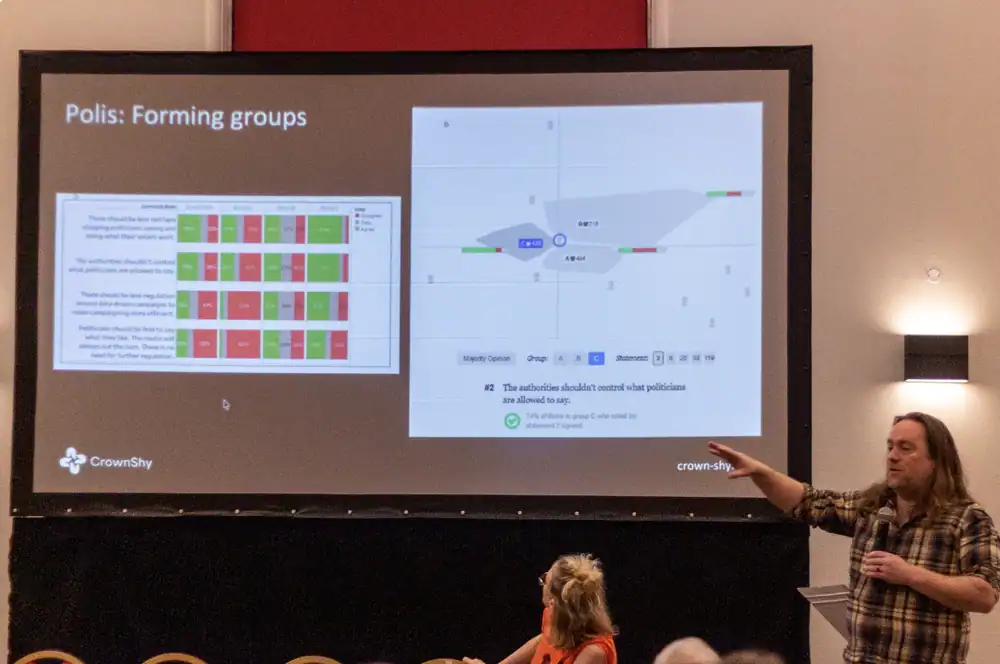

It combined live audience participation to gauge levels of positivity, optimism or feelings of agency with the introduction of digital polling using the Polis, a technology from Crowd Shy. Polis is “a real-time system for gathering, analysing and understanding what large groups of people think in their own words.”

In a world saturated with negativity, dominated by the rage economy and with a social media that runs on the fumes of binary disagreement, Polis seeks to find places of common ground. New ReDo describes Polis like this: “Polis uses open source, copylefted machine-learning technology to run online anonymous conversations. These facilitated conversations are living, breathing, thinking affairs, unlike all other survey tools before it. Polis has been used to seismic effect in Taiwan, revolutionising decision-making, whilst quelling antagonism.”

“Polis allows all voters to anonymously suggest statements and for all voters to vote on all statements. Polis then finds the consensus points and the cohorts within a group of people. Polis allows shy people (like me, believe it or not) to ventilate their thoughts. Polis is laser-focussed on finding the very best ideas, not the ideas most shouted about.”

The Spring group, which hosted the Celtic Connections event believe that Polis might be a way to enhance democracy in Scotland, and is already running a pilot project in Bressay, Shetland.

You can take part here: Polis.

Dùthchas

But this event was not all about digital boffinery. I explored some reflections on the issues around the Power Shift which you can read here. Music was supplied by E.M. Kane and friends and poetry by the Makar, Pàdraig MacAoidh. His presentation explored the relationship between (gaelic) language the individual, community and place. He said:

“Traditionally there were three different ways in which a person could be ‘placed’ within Gaelic culture: through dùthchas, or where you are from, your native place; dualchas, or who you are from – your kin; and gnàthas, measured against the norms of personal and social behaviour. So the Gaelic question ‘Cò às a tha thu?’ [‘Where are you from?’] is literally ‘Who are you from?’ – as a child I once, wrongly, answered it with ‘mac John Angus Alaig Rodaidh’, my patronymic.

And the common imperative ‘Cuimhnich cò às thu’ [remember who/where you are from], delivered to those who were emigrating, contained a whole host of obligations and weighted expectations.

What to do with this knowledge? Can this be carried over into contemporary discussions about land, place, renewable energy in Scotland? I’m wary of this: cultures and languages, like the natural world, can be viewed as resources and strip-mined, the topmost layer extracted and exported for consumption elsewhere.

This does not seem satisfying. It can lead, on one level, to slightly jarring Gaelic names of restaurants in the city (those oddly disconnected genitives) or misspelt tattoos (which direction does the accent go?); on another it can lead to a desire – expressed from the 1870s onwards at least – that Gaelic should, like Latin, be treated as a dead language, not spoken but used as a resource to give depth and nuance to other languages, primarily this one here we’re communicating in.

The act of taking meaning out of context, of stripping words and ideas from one language and transporting it into another is entirely at odds with the deep imbrication of value that MacAulay describes.

And of course I’m wary of this too – growing up on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis there was a suspicion, mostly rightly I suspect, of decisions being made in committee rooms and board rooms in London, Glasgow, Edinburgh, even Stornoway, decisions being made for or over the people who live in places, rather than by them.

And rightly there was a suspicion also about the voices of those who would pontificate about the islands without having lived on them for almost 30 years – the voices of people like me.

What does this all mean? Well, yes, there needs to be even more of a shift to local decision-making, land ownership, possession of the means to profit from renewable energy, more local power which will come with more local responsibility, a mature and serious democracy that involves as many people as possible in making decisions, sometimes tough ones, about the places they live in.

Without those places being seen, from somewhere else, primarily as a resource, with the need for a sustainable and – why not? – even prosperous future for the communities that live there.

There is a Gaelic proverb often used in articles of this type which makes the point that the natural world should be seen as a common good, not private property: “Slat à coille, bradan à linne, fiadh à fireach – trì ‘mèirlean’ às nach do ghabh Gàidheal riamh nàire” [A rod from a wood, a salmon from a pool, a deer from rough ground – three ‘thefts’ no Gael was ever ashamed of].

But, of course, this all has to be done sustainably too (only one salmon, please), and in the age of microplastics and nuclear waste it perhaps needs to be extended to the understanding that what we put into the natural world should be carefully thought through, as well as what we take out. Those ‘norms of social behaviour’ are always changing, and we should be careful that those changes are positive – and ideally bring people together.”

Knowledge Exchange

After Pàdraig MacAoidh came a panel of experts with Josh Doble from Community Land Scotland, Connor Watt from Platform and Indra Adnan from The Alternative.

Indra introduced the idea of ‘Fractal Organising‘ where small groups of citizens working together in deeply relational ways at community level, pattern match with others doing the same across the region, country, even globe. Technology makes it possible for them to connect, share information and grow the narrative, prompting quantum social change.

Josh shared this killer fact that: in Scotland, 64 per cent of people would support a community-owned energy development in their area, but only 40 per cent support a private enterprise.

Connor suggested that, from his work with oil workers in Aberdeen for Platform, there’s a bit of mythology that oil and gas workers are against renewables when his experience is that many are very open to the idea of transitioning into the renewables industry.

This idea of ‘knowledge exchange’ is a key part of the forum that the Spring Collective are trying to develop, to enrich audiences and inform communities.

At the interval, audience members were asked to suggest scenarios for improvisation, hilariously played out by Pippa Evans and Simon Sharkey.

There followed a Mapping Game led by Pat Kane from The Alternative. This invited people to find their place on a spectrum of opinion along a line between, at one end, Positive about the future of Energy in Scotland and, at the other end, Negative about the future of energy in Scotland. People were then asked to explain why they had chosen that position. This was then developed to create a second perpendicular axis and people were asked to reconsider their position.

The project aims to reconsider and reconceive what political meetings look and feel like, with participation as the defining feature, and drawing on the expertise of ordinary people, while combining conviviality, song, poetry and provocation to create an altogether different experience.